Bo Eric Beuthner1,2, Manar Elkenani1,2, Katja Evert3, Julian Mustroph4, Tim Seidler1,2, Elisabeth M. Zeisberg1,2, Gerd Hasenfuß1,2, Miriam Puls1,2, Karl Toischer1,2

1 University Medical Centre Göttingen, Department of Cardiology and Pneumology, Georg-August University, Göttingen, Germany

2 German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), partner site Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

3 University of Regensburg, Institute of Pathology, Regensburg, Germany

4 University Medical Center Regensburg, Department of Internal Medicine II, Regensburg, Germany

Background:

Recent studies have reported a relevant co-prevalence of severe aortic stenosis (AS) and cardiac amyloidosis (CA) with varying results ranging from 6 – 16 %. Although histological assessment of CA using congo red staining of endomyocardial biopsies remains gold standard for diagnosis of CA, no studies exist that use histology to screen for CA in patients undergoing TAVR.

Aims:

To histologically assess the incidence of concomitant CA in patients undergoing TAVR. Furthermore, we aimed to analyze the impact of co-prevalence of AS and CA on VARC-II defined complications and clinical outcomes.

Methods:

We retrospectively identified 166 patients undergoing TAVR at the University Medical Centre Goettingen between 01/2017 and 03/2021 who consented the biopsy of five endomyocardial samples using a 6F biopsy forceps. Biopsies were stained using congo red dye and analyzed using polarized light by one pathologist blinded to clinical data.

Results:

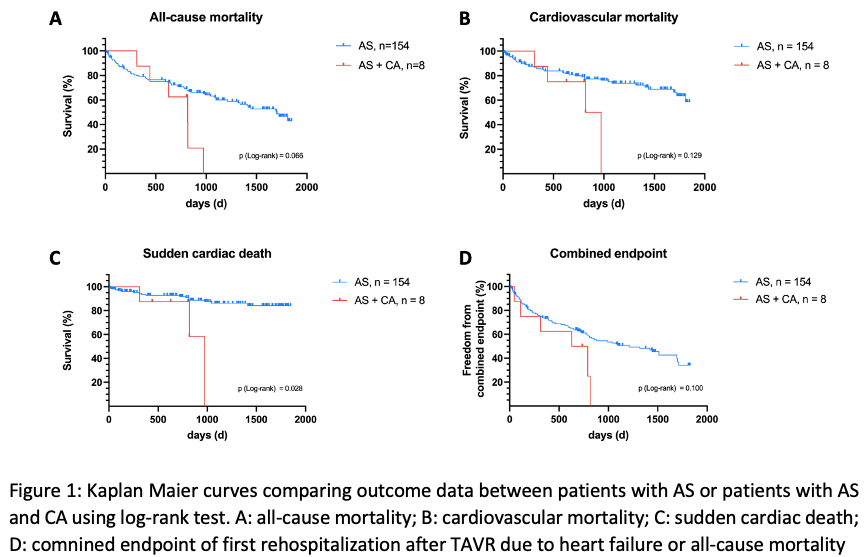

Co-prevalence of CA and AS was 4.9 % with interstitial amyloid deposits detected in all 8 patients. At baseline, AS+CA patients had significantly more atrial fibrillation (42.2 vs. 87.5 %, p=0.022), higher NT-proBNP levels (4476.48 vs. 9035.28 ng/l, p=0.034) and a lower voltage/mass ratio (0.015 vs. 0.0073 mVm2/g, p=0.022) than AS patients. On echocardiography, co-prevalence of AS and CA was associated with significantly lower transaortic gradients (Pmean 38.00 vs. 17.50 mmHg, p=0.004), lower stroke volume index (33.15 vs. 25.68 ml/m2, p=0.007), and lower left-ventricular wall thickness (PW 13.00 vs. 15.88 mm, p=0.012). AS+CA patients experienced significantly more often postprocedural acute kidney injury (AKI, 13.1 vs. 50.0 %, p=0.018) and displayed overall poorer clinical benefit after TAVR. Yet, only one AS+CA patient (12.5 %) died within the first year after TAVR. AS+CA patients died significantly more often from sudden cardiac death after TAVR than AS patients (p (log-rank test) =0.028, HR: 4.084, 95 % CI: 1.166 – 14.303).

Conclusion:

Conclusion:

Co-prevalence of CA and AS was lower than expected at 4.9 % and associated with higher incidence of postprocedural AKI. Despite excellent one year mortality, AS+CA patients died significantly more often from SCD calling for further studies examining potential benefits of prophylactic ICD implantation in AS patients with concomitant CA.

Outlook:

In a subset of patients, we are currently investigating proteomic differences between AS patients with and without concomitant CA (4 AS+CA patients vs. AS patients after propensity score matching).

https://dgk.org/kongress_programme/jt2023/aP1332.html